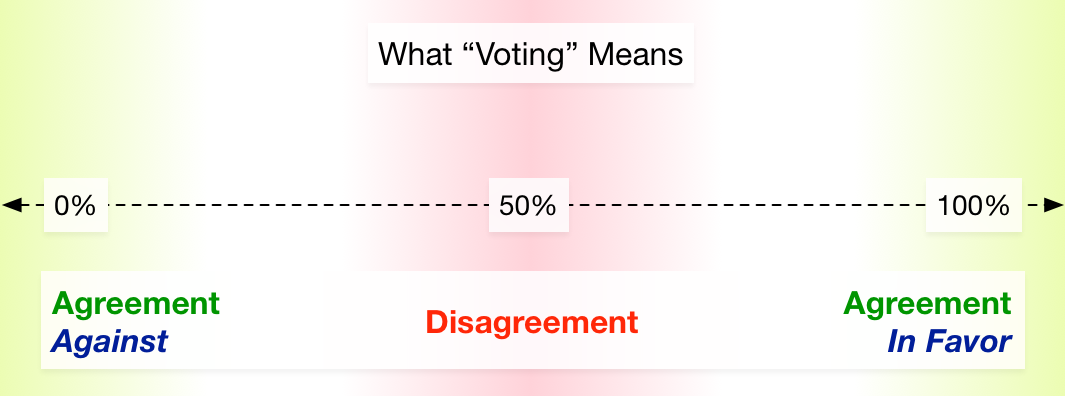

It’s not completely clear how this happened, but somewhere in our history it was decided that, “A majority voting in favor of something indicates the presence of agreement, and we should proceed ahead.”

Where this notion comes from, and the (mis)information surrounding majority rule, is the subject of this and a future post.

Welcome to the Group Income blog!

Group Income is a fair, efficient, decentralized Basic Income system for you and your friends.

And this is our blog where we will provide semi-regular project updates and discuss the concepts and design decisions that are going into the code.

We’ll start by diving into the concept of voting, a process that plays a critical role in Group Income and elsewhere.

Like many people, you’re probably OK with, or at least used to, the idea of majority rule. But have you given thought to why we use it, and what it means?

Majority Rule And Group Agreement

It’s a common assumption that “51% in favor of Proposition A,” implies “We’re in agreement that Proposition A should pass.”

However, that is only partially true if the group decided—formally and beforehand—that every proposal, no matter how divisive or controversial, will be decided by majority rule.

Even then, the “We” of “We’re in agreement” only refers to half the group. From the outside, it appears as if two groups are in discord with one another:

Perhaps this method of making collective decisions is not always the best way to go?

If we think of a group as a collective that acts in the interests of its members (for example, a family), then a proposal that receives 51% support indicates: “The group is in almost perfect disagreement on whether or not to approve the proposal.”

Let’s consider some examples of real-life group-decision making.

House of Representatives

We tend to think of the House of Representatives in terms of a single entity, so we’ll say that a bill “passed the House” if it received 52% support. In reality, it’s more accurate to say, “The bill passed half of the House, which is almost perfectly split as to whether or not the bill should become law.”

It’s also important to ask: who is affected by the decision? Is it just the group members, or those outside of it? If outsiders are affected, how many and in what way?

In the United States, a “Congress majority” is 0.00008% of the U.S. population, and this group (along with a few others1) decides the rules of behavior for about 300 million people outside of it.

Is this a good idea? Are there better alternatives? And if so, what are they?

These are some of the questions we’ll be exploring in our posts. We invite you to think about them and share your thoughts with us in the comments.

House of Representatives vs Moviegoers

Consider your group of friends. You have a decision to make, “What movie should we go see tonight?” What do your friends do if some want to see Movie A, while others, Movie B?

You might:

- Negotiate or debate. This often happens in small groups (2 to 4 members).

- Do a majority vote and give a concession to the losing side (perhaps to watch the other movie next time).

- If the group is big enough, the group can split up and each side can see the movie it wants.

How does the above compare to what goes on in the House? We’ll list a few observations below, feel free to comment with more:

- The moviegoers are friends.

- The moviegoers’ stakes are much smaller because their decision doesn’t impact 300 million people.

- The moviegoers group is much smaller (2-10 members vs. 435 voting members in the House).

- For the moviegoers, splitting up instead of voting is an easy choice that can satisfy both sides. The House of Representatives cannot pass two conflicting laws, and if it does it’s usually considered a problem.

- The majority vote in both situations involves making concessions to the losing side, at least sometimes.

- The moviegoers do not consider their decision a job. They’re not paid to decide, they decide, and then pay.

- Going to the movies is unlikely to follow a formalized schedule, nor are there formal proceedings to follow.

- The moviegoers do not go in to the decision expecting a battle, and their decision-making doesn’t take as long.

- Moviegoers often allow individuals limited power to fully veto a majority decision (e.g. “I’ve already seen it” or “Can’t handle a ____ movie right now.”) House of Representatives requires convincing other reps, or hoping for Presidential veto.

- Moviegoers often allow each individual a chance to voice their preference and reason, especially if there’s not consensus. There’s simply no time to do this on every vote in the House of Representatives.

It’s also worth noting that most moviegoers seem happy after their decision.

Consensus — AKA supermajority rules

Sometimes majority rule seems like a suitable voting rule to use. Other times, especially when stakes are very high and very personal, a rule that requires greater group agreement is preferable.

These types of rules are called supermajority rules or consensus rules, and they’re used in various high-stakes situations:

- A jury that’s deciding whether or not someone is guilty of murder. After all, who wants to risk being directly responsible for incorrectly sentencing someone to life in prison or death?

- Modifying a Constitution or the Bill of Rights.

- The protocols that power the Internet and Bitcoin.

See also Christopher Allen’s wonderful overview of different types of consensus rules.

There are also submajority rules, but we’ll cover those another time.

Voting In Group Income

In Group Income, voting plays at least four important roles:

- Deciding the Group’s mincome level.

- Deciding whether or not to add a member.

- Deciding whether or not to remove a member.

- Deciding whether or not to change the rules.

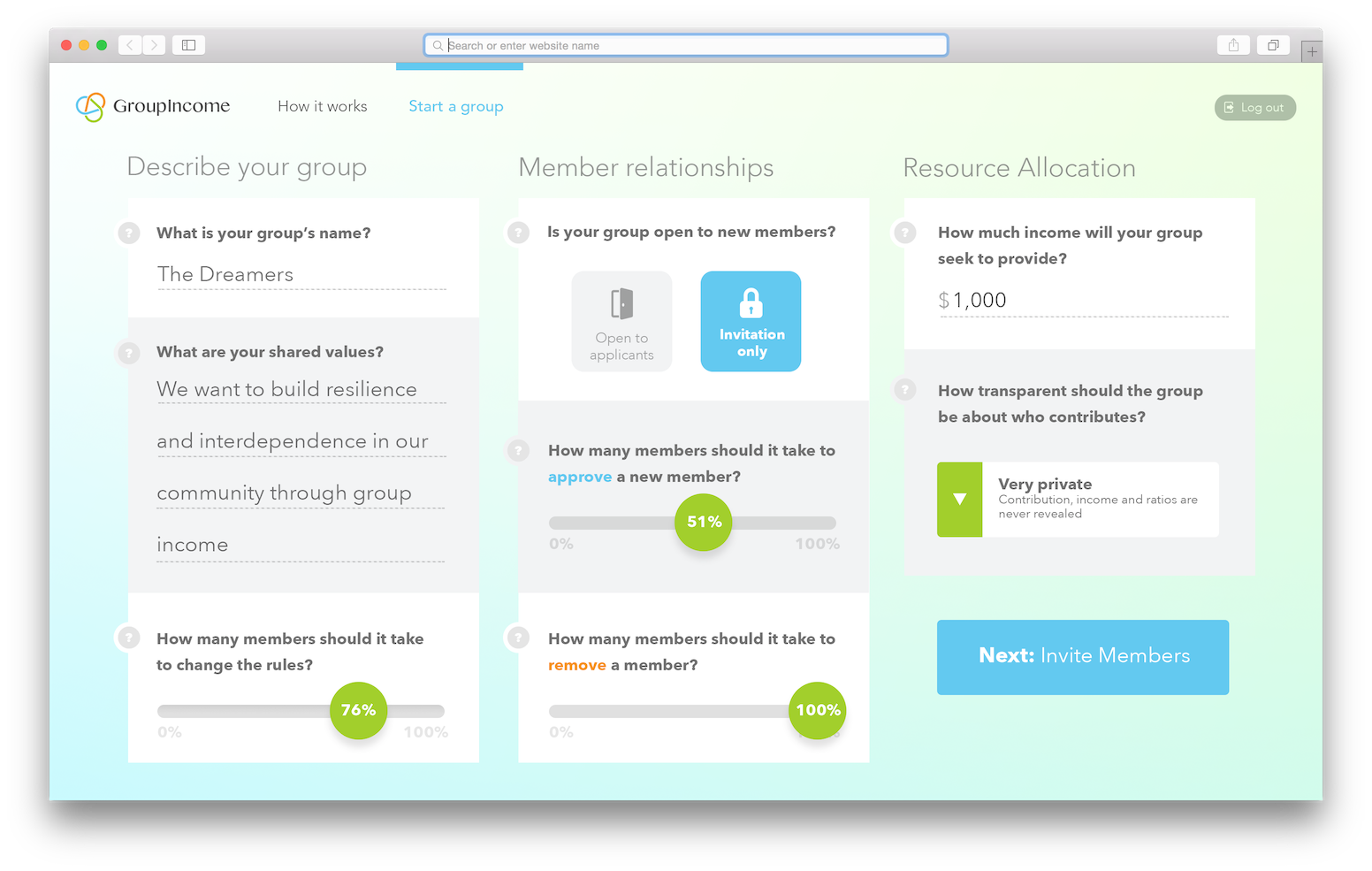

Here is one of our mockups for the UI that we’ll be experimenting with when users create a group. You can think of it as setting up the Group Constitution:

A few notes:

- Voting rules are specified generically by voting thresholds. Simply move the slider to 51% to choose majority-rule.2

- You can set different rules for different actions.

- Once you set the rules, you cannot change them. Not without a vote, at least. Those who join your group are giving you their consent to abide by the rules, and you, in turn, are giving your consent to them that you won’t modify those rules without receiving approval from the group. Our goal is to ensure that nobody (not even the developers of Group Income) can change the rules without following the rule for changing them.

- There are two types of voting thresholds to consider: the turnout threshold and the abstention threshold. The former only cares about those who make a decisive vote for or against, while the latter counts abstainers as a third type of vote, thus increasing the likelihood of impasse.

Considerations When Designing Voting Systems

- What voting threshold is appropriate for what types of decisions? In other words, do you use submajority, majority, or supermajority rules?

- How do you count those who abstain from voting? In other words, do you use the turnout threshold or the abstention threshold in making the decision?

- Should there be a minimum number of “yes” votes, regardless of the turnout threshold, before a motion is allowed to pass?

- How much time/notice needs to be given prior to a vote?

- How are votes counted?

- Is voting anonymous (like during an election) or out in the open (like in a board meeting)?

- Can votes be delegated to someone else? If so, is it a liquid democracy (like DemocracyEarth)?

- How does the group size affect the voting system that’s used?

- Do you need to guard against the sybil attack?

- Do you weight votes based on some criteria?

- Does your voting system account for someone’s knowledge-of or vested-interests-in the issue?

- Can people express how important an issue is to them (e.g. quadratic voting)?

- Can people order their preferences among a set of options to avoid “splitting of the vote” vote manipulation?

- Are vetoes allowed, and if so how are they handled?

- Who is allowed to make proposals in the first place?

- Are people outside of the voting group affected by decisions made by the voting group?

- Do you allow any proposal or do you handle them differently depending on their actual content?

- Is your voting system secure?

And remember, some types of decisions are better decided without a formal vote!

That’s All For Now! Happy First Blog Post! 🎉

Thanks for reading our first blog post! We hope you’ve enjoyed it!

If you like what you see here and are interested in participating in this project (whether as a contributor or to take part in pilot studies), please get in touch on Twitter, Slack, or on our forums!

Post by Greg Slepak, with help from Andrea Devers, Trent Oswald, and Simon Grondin.

More project updates, hackathons, and blog posts coming your way!

Up Next: We’re taking on the fascinating world of Social Choice Theory. How much of it is true? How much is a crock?

Please empower our work by donating!

(BTC / ETH welcome!)

Footnotes

-

Many other bodies (like the FDA, the DEA, etc.) received their “rule making” powers from Congress, and this has led to an explosion of rules that Americans must follow, like the allowable font size on a gallon of sherbert. ↩

-

Technically, 51% is not the “threshold” (as we define the term). We use “threshold” to mean the point above which a motion passes. However, in the UI itself, it may be easier to explain this concept to users just by phrasing the instructions as, “How many members should it take to approve an [action]”. ↩