In our previous post, we explored the meaning of voting and what it takes to make a good voting system. In this Part 2, we hope to convince you that what you’ve been told about majority rule is not only untrue, but harmful.

- Voting Is Fairly New

- A Series Of Unfortunate Decisions

- May’s Theorem

- Terms & Conditions

- Condition I: “always decisive”

- Condition II: “anonymity” or “egalitarian”

- Condition III: “neutrality”

- Condition IV: “positively responsive”

- Even Academics Are Misled By May’s Theorem

- Confusion Over ‘Status Quo’

- Confusion Over ‘Majority’

- Confusion Over ‘Minority’

- Summary

Voting Is Fairly New

Voting, and especially voting that involves a significant portion of the population (which we call Democracy), is a fairly new concept. Most online descriptions of voting and democracy-ish type systems point to either Greece or India as their earliest examples, followed by Rome. These systems still excluded much of the population from having a say in their society, but they involved a lot more voting than the dark ages and monarchies to follow. It seems it really wasn’t until around the time that a few colonists decided to leave one of those monarchies and eventually establish the United States that voting began to resurface around the world in any serious capacity.

So, the practice of voting, and especially the idea of voting systems, remains a fairly new and poorly understood, unexplored phenomenon.

A Series Of Unfortunate Decisions

Whether it be the election of a tyrant, the passing of prohibition, or the invasion of Iraq, our world is deep with the painful consequences of poor collective decision-making brought about through voting.

In each of these decisions, the concept of voting and the notion of a majority have played pivotal roles. It does not seem to matter whether a country is run by democracy or dictatorship: every major political system has representative nations who’ve made decisions where everyone was left worse off, including the decision makers.

In spite of failing to prevent various disasters, the concept of majority rule has not only survived but has maintained a prominent position in our day-to-day decision-making systems.

When does majority rule work? When does it fail? And why do we use it so often? These are some of the questions we’ll be exploring today.

May’s Theorem

If you’ve ever wondered why majority rule is so prominent, you’ve undoubtedly stumbled upon May’s Theorem. It is found in almost every justification for majority rule.

Most descriptions of the theorem look something like this:

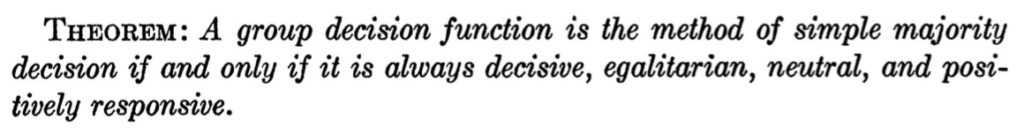

Theorem (May 1952): An aggregation rule satisfies universal domain, anonymity, neutrality, and positive responsiveness if and only if it is majority rule.

— Stanford’s Encyclopedia of Philosophy

However, the original theorem, as written by Kenneth May in 1952, looks like this:

Are either of these expressions of the theorem true?

To find out, we’ll examine the four “Terms & Conditions” of May’s Theorem, and explore how bad English and good math can produce a theorem so misleading, that it might as well be untrue.

Terms & Conditions

May’s Theorem says majority rule is the only rule to satisfy these four conditions:

- Condition I: “always decisive”, sometimes called “universal domain”, and sometimes missing entirely (as on Wikipedia)

- Condition II: “egalitarian”, sometimes “anonymity” or “anonymous”

- Condition III: “neutral”

- Condition IV: “positively responsive” or “positive responsiveness”

But … what are they? Why does Wikipedia not mention the first condition? How are “egalitarian” and “anonymous” the same thing? Is it possible to prove that a voting rule is “egalitarian”? What do “neutral” and “positively responsive” mean? What is the real significance of this theorem? How does it help us decide when to use majority rule? (Does it?)

To answer these questions, let’s look at its context and then examine the four conditions.

Context of May’s Theorem

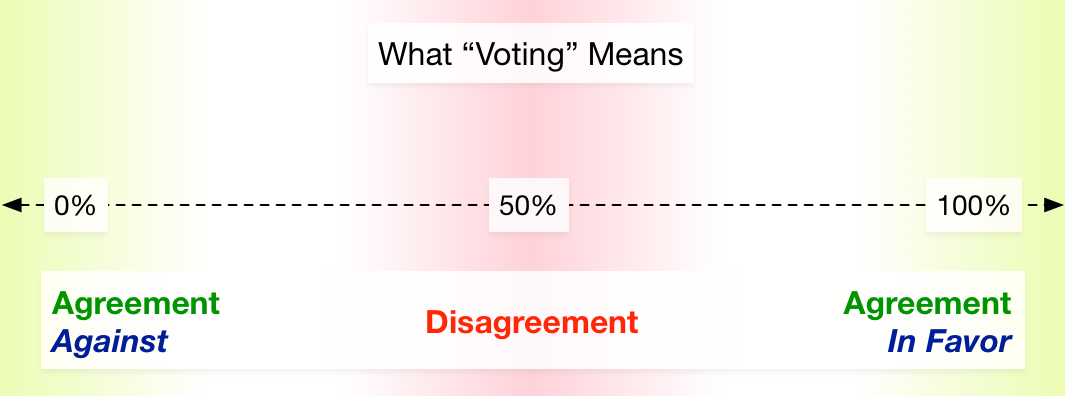

May says the theorem is about a vote between “two alternatives” and . As we’ll see, this isn’t exactly true. More accurately, May’s Theorem concerns itself with a proposal , the status quo ,1 and a third option we’ll call z.

May considers various group decision functions that could be used to decide between the choices and , and focuses on one with a 50% threshold called “majority rule”.

Let’s define these terms:

- Group decision function: A voting rule that tallies votes in favor or against a proposition and outputs 1, -1, or .

- Threshold or turnout threshold: The percentage of votes in favor above which the motion will pass, when votes of (indifference or abstention) are ignored.

- Abstention threshold: Like threshold, except votes of are counted and are used to increase the likelihood of impasse. So, with a 50% abstention threshold and the votes , the outcome is not but either or , depending on the decision function. Abstention thresholds are similar to supermajority rules but are specifically useful when it makes sense to encourage a high turnout.

- Turnout: The percentage (or number) of voters who did not abstain from voting.

- Unweighted: 1-person-1-vote style voting (as opposed to 1-dollar-1-vote style voting).

- Majority rule: Unweighted voting rule with a threshold of 50%.

- Supermajority rule: Unweighted voting rule with a threshold >50%. Typically, 2/3 or more.

- Submajority rule: Unweighted voting rule with a threshold of <50%.2

May assigns meaning to the output of the group decision function like so:

We assume n individuals and two alternatives and . Symbolizing “the th individual prefers to ” by and “the th individual is indifferent to and ” by , we assume that for each one and only one of the following holds: , , or . With each individual we associate a variable that takes the values respectively for each of these situations. Similarly, for the group, we write according as , , or , i.e., according as the group decision is in favor of , indifference, or in favor of .

In plain English: the individual votes and the group decision can have one of three values:

Had May recognized the significance of as an outcome, the world might have turned out differently.

— The Missing Third Alternative

May mapped to mean “in favor of ”, to “in favor of ” (against ), but did not map an outcome for . Instead, he simply referred to it as “indifference” or a “tie”.

What is the outcome in this situation? In the real world, different groups have different answers. They might proceed with a tie breaker, arbitration, negotiation, or some other procedure. These are often very meaningful and important activities, and their result is not always represented by or . Furthermore, the “tie” itself as an outcome, is neither nor . If it were, it would imply or , which is nonsense in both English and math.

May’s confusion around results in an even more serious problem, for it can be used to represent semantically opposite concepts:

| Votes | Possible meaning |

|---|---|

| “Nobody cares” aka “Indifference” | |

| “Everybody cares” | |

| “Some care” |

Our previous post explains why does not (typically) mean “indifference” but is indicative of disagreement:

However, even if we used the turnout to measure “indifference”, that is also not necessarily a reliable way of representing indifference. For example, a low turnout in a presidential election might mean that people do not care, or it could mean that they care but do not approve of either option.

During our discussion of Condition IV, we will see why it can be more helpful to think of z as a “no-win” outcome, rather than “a tie”.

Onward!

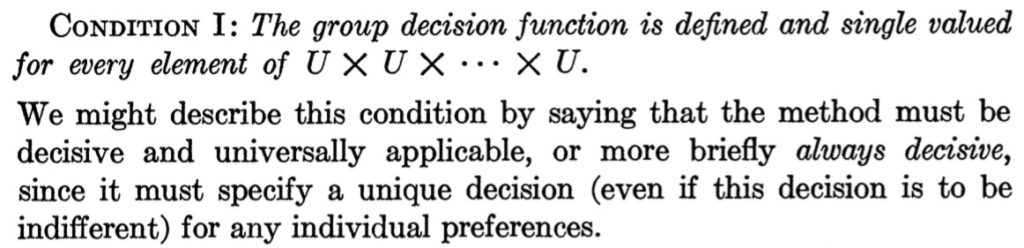

Condition I: “always decisive”

Here’s a screenshot of Condition I from May’s paper:

That may sound fancy, but all it says is: “A group decision function is a function [that outputs -1, 0, or 1].”3

May gives the following example of “something” that does not satisfy this condition:

for for

We say “something” because the above, having multiple values for , is called a multivalued function, which is not a function:

In the strict sense, a well-defined function associates one, and only one, output to any particular input. The term “multivalued function” is, therefore, a misnomer because functions are single-valued.

Now we understand why Wikipedia probably left out the fairly uninteresting Condition I. After all, the context of the theorem is about whether a proposal passes, and a proposal cannot both pass and not pass at the same time. Even a tie maps to a single output.

As we’ll see, each one of May’s conditions comes with an English description that is, to varying degrees, an unfaithful representation of the math. Condition I is the least misleading condition, but it’s still worth considering how it could be misunderstood.

Consider May’s example of a jury decision rule, which he says is “always decisive”:

or according as or otherwise.

Is a hung jury therefore “decisive” when it cannot agree upon a verdict”? We’ll forgive May this one time and say they’re “decisive about their indecision.”

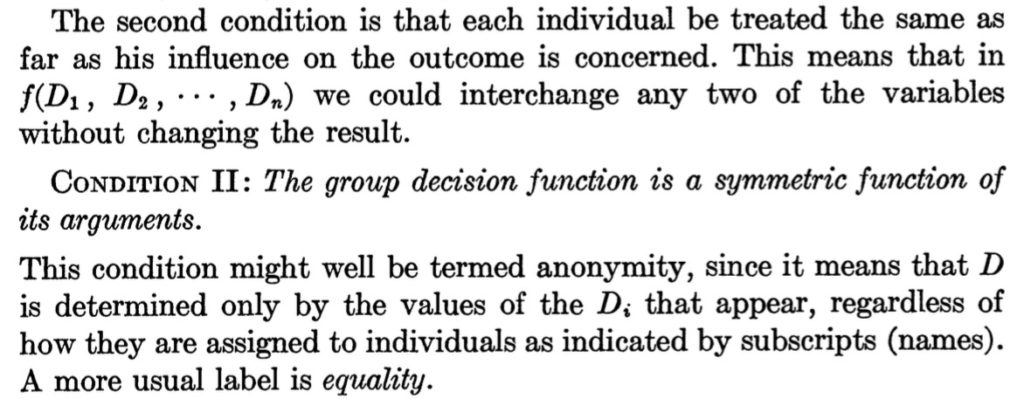

Condition II: “egalitarian” or “anonymity”

The term “egalitarian” only appears once in the entire paper: in the theorem statement itself. We know the terms “egalitarian” and “anonymity” refer to the same thing by process of elimination and the reference to “equality”:4

This simply says votes are unweighted and their order doesn’t matter. That is, we’re focusing on decision rules of the 1-person-1-vote variety (and not, e.g., the 1-share-1-vote variety).

The word “anonymity” does not mean votes are anonymous in the sense of requiring a hidden ballot (a fully transparent vote would still satisfy Condition II), nor does it necessarily mean that majority rule is egalitarian.

Egalitarianism is the belief that people deserve equal rights and opportunities, but does that imply it is unegalitarian for a company to give less voting power to an outside shareholder with 0.000001% ownership in the company than to its CEO, who owns 30%? And is it suddenly “egalitarian” if a group votes to enslave another group using majority rule?

Clearly, it does not matter whether or not majority rule is used in these situations, the words “equal”, “anonymous”, and “egalitarian” do not apply. Per egalitarianism, people have an equal right to use whatever voting system they feel is appropriate to their situation, as long as they do not deprive others of that same right.

Therefore, the math of Condition II is not represented by the English.5

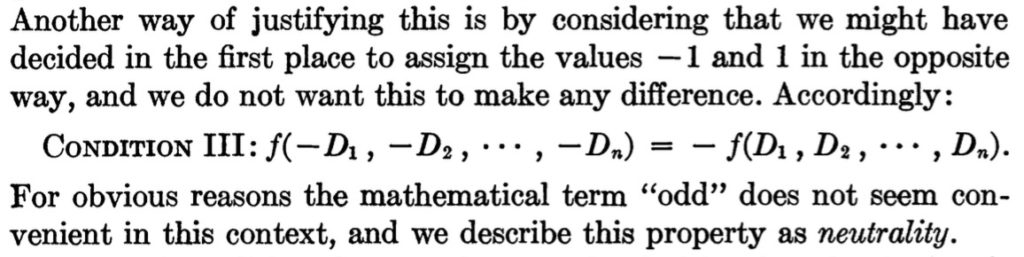

Condition III: “neutrality”

Condition III is the most frequently cited justification of the four conditions:

It is Condition III that’s referenced when someone says majority rule is “neutral with respect to the status quo”. For example, Adrian Vermeule’s review of a book on Social Choice Theory says:

A formal result called May’s Theorem shows that where a group must choose between two options, simple majority rule is the only approach that respects equal treatment of voters (so-called anonymity) and equal treatment of the options before the group (so-called neutrality). By contrast, supermajority rule in its ordinary form violates neutrality, because it privileges one of the options—the status quo option of leaving everything as it is, an option that will become the group choice so long as a sufficient minority supports it.

But is that true?

Again we find May’s English betraying a far more complicated reality.

In the following two scenarios, the status quo starts out as “America in 2016”. Consider how the status quo changes after proposal passes via majority rule:

- Scenario 1: A vote is held on proposal to “Make America Great Again by giving everyone a free makeover.” After passes, everyone looks slightly better for a day.

- Scenario 2: Now suppose is a proposal to “Make America Great Again by forcibly sterilizing half the population.” Again, we use majority rule because of all of its supposed wonderful mathematical properties, and, thanks to a heaping of state propaganda, passes and in doing so radically changes the course of history.

It seems silly to suggest that in both scenarios the status quo and proposal are “equally privileged”. We note the following factors, all of which can play a more significant role in determining the status quo than the voting threshold:

- The difference between the existing status quo and the proposal. Compared to mandatory castration, few would object to a free makeover (today, at least). Therefore, whether the threshold is 30% or 60%, Scenario 1 seems far more likely to pass than Scenario 2. Even if the proposal in Scenario 2 passed, if it did so outside the context of a fair vote in a direct democracy that would not necessarily mean the reality of would pass. Instead, it’s possible the new status quo would be neither nor , but .

- Who chooses the proposal, who votes on it, and who is affected by it. “Majority rule” is supposedly used in Congress to decide whether or not a law passes, but a Congress majority is only 0.00008% of the population. Laws, however, affect not only Congress but all 300+ million Americans. It does not matter, therefore, what the “options before the group” are or what the voting threshold is — the outcome, and therefore the status quo, will still be biased in favor of the interests of a microscopic fraction of the population.

Increasing the voting threshold obviously makes it more difficult for proposals to pass, but as we’ve seen, that does not mean a 50% threshold ensures a voting rule does not privilege some outcome over another.

In truth, every voting rule and voting system privileges some status quo over others, no matter the threshold used. And, we should want to privilege some status quos over others: the ones that make life work well for the greatest number of people while minimizing harm.

As we’ll discuss in the next post, there are many situations where it only makes sense to use a high voting threshold. But: who chooses the proposal, who votes on it, and who is affected can matter a great deal more than the threshold in determining the status quo.

If we care at all about the status quo, we have no choice but to pay attention to these other factors as well.6

It’s nice that May somewhat acknowledges this, although few seem to have noticed his footnote:

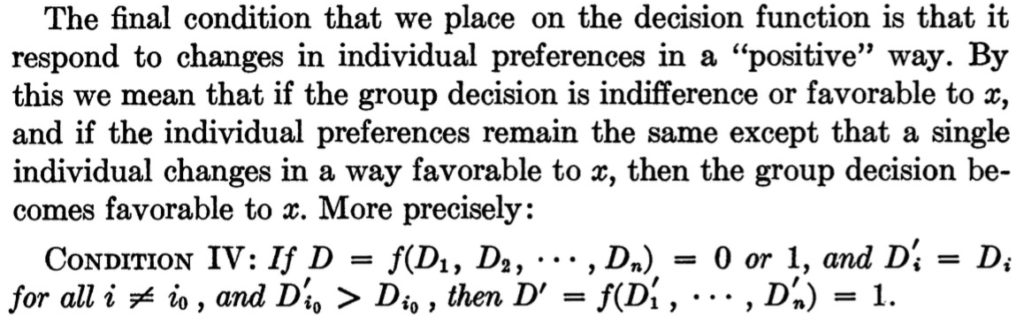

Condition IV: “positive responsiveness”

The final condition is a nice segue to understanding the real difference between majority rule and other voting rules, although it is by understanding the misunderstanding of the condition that we get there:

In other words, if a group is initially “indifferent” towards a proposition and someone changes their vote to be more favorable, the proposition succeeds.

That probably sounds very sensible. However, as noted earlier, May’s description of Condition IV is incorrect because May’s math is incapable of expressing the concept of indifference. On the other hand, Wikipedia does accurately describe the math. Note the lack of any mention of “indifference”:

Condition 4. If the group decision was 0 or 1 and a voter raises a vote from −1 to 0 or 1 or from 0 to 1, the group decision is 1. (positive responsiveness)

We can piece together a better understanding of Condition IV by returning to our discussion about the misunderstood result, and by considering the examples May gives for voting rules satisfying all but one of the four conditions:

- May’s so-called “always decisive” jury decision rule violates only Condition IV:

or according as or otherwise.

- What May calls the “familiar two-thirds majority rule” violates only Condition III:

according as is less than, equal to, or greater than zero.

In neither example does represent “indifference”. A jury is not “indifferent” when it is hung, nor is a group that’s split 2 to 3.

So what to make of ?

Stanford’s Encyclopedia of Philosophy makes a distinction between two kinds of supermajority rules, referring to the type May gives as “asymmetrical” because occurs only at the voting threshold. The other type, “symmetrical”, is more like the jury voting rule because it increases the likelihood of a “no-win” outcome where there is no winning side.

The movie 12 Angry Men explores the significance of the “no-win” situation and how, thanks to the emphasis unanimity places on (and the related principle of reasonable doubt), a single obstinate juror is able to persuade the rest into making the correct decision — thereby saving the life of an innocent man.

The effect of Condition IV is to reduce the opportunity for the “no-win” outcome that represents, and therefore it reduces opportunities for options like honest debate, negotiation, and arbitration. A successful bribe to a single member can be enough to declare half the group “the winner” and the other half “the loser”, even though there’s little difference between 50-50 and 49-51.

Even Academics Are Misled By May’s Theorem

By this point, you should understand how May’s Theorem misled many people into reaching the mistaken conclusion that “math” says majority rule is “the best” voting rule.

This misunderstanding even afflicts some parts of academia, where we find declarations such as the following (taken from the abstract of a University of California, Irvine paper):

This paper demonstrates that majority rule offers more protection to the worst-off minority than any other system, in that it maximizes the ability to overturn an unfavorable outcome. It is known (May 1952, Dahl 1956) that majority rule is the only decision rule that completely respects political equality.

Although that is untrue, it’s still a relevant contribution to the prevalence of majority rule today.

Confusion Over ‘Status Quo’

The word “status quo” is frequently misunderstood in discussions about voting rules, and especially in discussions about May’s Theorem. Though it may certainly play a contributing role, the status quo has never been contingent solely on the threshold of some voting rule.

It is incorrect to imply that if does or does not pass, some static thing called (the “status quo”) remains or changes in the prescribed way.

Whether you live in a dictatorship or a “democracy”, the status quo is always changing—by itself. Today’s reality might include a fearsome dictator who tomorrow chokes on a pretzel, ending years of oppression without any voting involved. Likewise, just because a law is on the books doesn’t mean that it has meaningful influence over the status quo. Most people have approximately zero awareness of the laws they supposedly should be following, and the few who are aware frequently choose to ignore them. When prohibition passed, alcohol abuse not disappear, in some cases the problem got worse.

What if the misrepresentation and misuse of majority rule biases the status quo towards one where poor decisions are the norm?

Confusion Over ‘Majority’

Sometimes there is confusion about what is or is not called “majority rule”. May’s paper seems to focus primarily on decisions that affect group members. He does not consider what happens when decisions affect people outside of the voting group.

We have to recognize that there is a fundamental difference between “majority rule” that affects only those who can vote, and “majority rule” that affects a population ~600,000 times larger than the voting group. These are so different that they deserve different terms. At the very least, we should not refer to the latter as “majority rule”.

Similarly, sometimes a “51% majority vote” is called “majority rule” when it is not. Per Condition II, shareholder voting, proof-of-work, proof-of-stake—none of these are majority rule.

Confusion Over ‘Minority’

Often, arguments for or against higher voting thresholds will confuse the notion of “oppressed minorities” with the mathematical notion of a minority.

Note the contrast between “oppressed minorities” and the following “minorities” of the mathematical sense:

- Those who think we should have ice-cream on Tuesdays instead of Wednesdays

- Everyone (as can happen in plurality voting)

When discussing “oppressed minorities”, thinking purely in terms of “50%” and “majority vs. minority” is unhelpful. After all, most “minority groups” are oppressed not by “majorities”, but by “minorities” like the following:

- Dictators (can have only 1 of them)

- The “ruling class” or “power elite” (aka plutocrats)

The message bears repeating: there are more factors to consider than simply the voting threshold.

Summary

The primary justification for majority rule—May’s Theorem—does not say (in math) what it claims it says (in English), and its descriptions in textbooks and across the web are misleading. Majority rule is not an “anonymous” voting rule, nor is it an “egalitarian” voting rule, nor is it “neutral with respect to the status quo”. What is called “majority rule” today is also often not.

This Wednesday — Part 3.

Post split up due to length.

Day after tomorrow we’ll cover the final topics:

- When Majority Rule Can Harm

- When Majority Rule Can Help

- Minority Rights

- Beyond Voting Thresholds

- When Voting Is Not Enough

- Avoiding May’s Mistake

- Repeating May’s Mistake For Great Profit

_Thanks to Simon Grondin, Andrea Devers, and Jason Krueger for reviewing this post, and to the members of r/math and r/askmath for their insightful feedback, with special thanks to RosaDecidua and wonkey_monkey. You can follow the author and Group Income on twitter.

A note

This post is the result of months of research and work involving 300+ revisions and several rewrites. We think it would be wrong to place it behind a paywall, but we’re very thankful for any support you can give, whether it’s financial, or simply a link back.

Footnotes

-

May did not explicitly state that refers to the status quo, but it is indicated by his four conditions and the implications (and problems) surrounding his theorem. If were something other than the “status quo”, his theorem would fall apart because majority rule’s “neutrality” would no longer be at all believable (it would be exactly not neutral, resulting in a move away from the status quo almost every time). ↩

-

Submajority rules are rare, but some argue there are good reasons to use them, and you’ll notice the well-known plurality rule fits our definition. Note also that using an abstention threshold makes less sense in the context of submajority rules. ↩

-

That last part comes from the definition of , found earlier in the paper: “It seems appropriate to call it a group decision function.4 It maps the -fold cartesian product onto , where .” ↩

-

Note that this is sloppy, bad math. Mathematical theorems must define terms precisely and then use them in a consistent manner. Instead, May plays word games with the reader, misleading them into believing Condition II implies majority rule is “egalitarian” or “anonymous” when the math implies neither. ↩

-

This “trick”—that of mapping misleading terms to math that works out—is considered by some mathematicians to be sufficient to declare the resulting misleading English of a theorem to be “true”. In our opinion, allowing lay persons to then walk away with an entirely untrue understanding, especially when it results in real harm to their lives (and then ), is severe professional negligence. Besides, if this were acceptable, one would be able to “mathematically prove” literally any English statement, no matter how absurd. ↩

-

We maintain a giant list of important considerations. ↩